by Alessandra Ressa

High above Trieste, on the edge of the Carso plateau, stands the Santuario Nazionale a Maria Madre e Regina di Monte Grisa. Visible from the city and from ships entering the Gulf, the sanctuary is both a landmark and a paradox: a bold gesture of modernist architecture, a product of wartime vows, a site of devotion, and a lightning rod for controversy. For the people of Trieste, it is never just another church.

The story begins in April 1945. With Trieste on the verge of collapse, threatened by retreating Nazi forces and partisan battles, Bishop Antonio Santin prayed for the city’s salvation. He vowed that if Trieste were spared from destruction, he would build a sanctuary to the Virgin Mary in gratitude. The city survived, and years later, in 1959, Pope John XXIII authorized the creation of a new national shrine. Soon after, the first stone was laid on Monte Grisa, and by 1966, the sanctuary was complete.

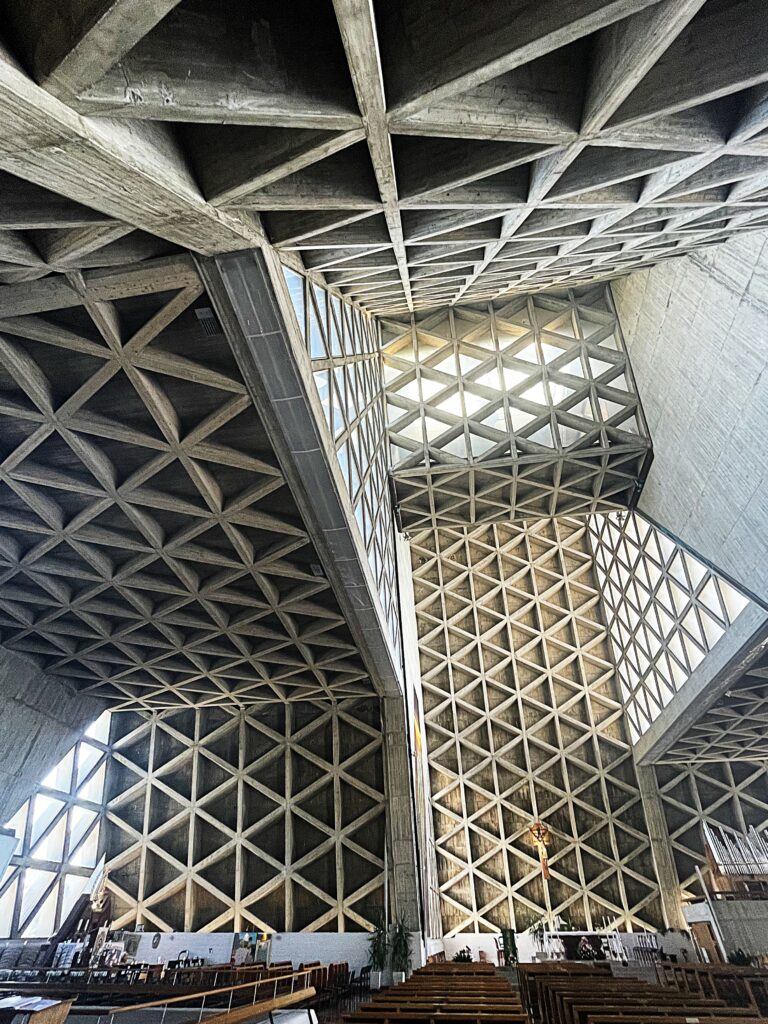

Monte Grisa was designed by Antonio Guacci, working from Bishop Santin’s sketches, and its geometry is unmistakable. Constructed almost entirely of reinforced concrete, the sanctuary is made up of triangular modules that evoke the letter M, a reference to Mary. This triangular motif dominates its facades, creating an angular, futuristic silhouette that contrasts sharply with the wooded slopes of the Carso. For the faithful, it is a symbol of protection and reconciliation. For architecture enthusiasts, it is a bold expression of post-war modernism. And for many Triestini, who view it from the city below, it is affectionately and somewhat irreverently called the formaggino — because its triangular structure resembles the soft, foil-wrapped cheese wedges given to children. The statue of Monsignor Santin today stands in perpetual struggle against the Bora, which at the most panoramic point of the site exceeds 100 km/h on particularly windy days.

If its form divides opinion, its location unites admiration. Standing at 330 meters above sea level, the sanctuary’s piazzale opens onto one of the most commanding views in the region. On clear winter days, the Adriatic sparkles all the way to Istria, while the rooftops of Trieste sprawl at your feet. The panorama is so striking that even those unmoved by concrete geometry often linger to take it in. Reaching the sanctuary is easy enough: city bus number 42 runs from Piazza Oberdan up the winding roads of the Carso, carrying pilgrims and casual visitors alike to the top, where the sudden vastness of the landscape makes the climb worthwhile. Beside the sanctuary, immediately after the entrance gate, begins a striking Via Crucis that winds through a lush forest filled with Austro-Hungarian trenches from the Great War. Following this path, you will reach the start of the popular and panoramic Napoleonica trail, the most beloved route among the people of Trieste.

Inside, the sanctuary contains two churches, one above the other, with light filtering dramatically through its concrete ribs. Pilgrims visit to pray before the Madonna, but even those without a religious motive are struck by the play of shadows and light, the vastness of space, the solemn atmosphere. For many, the experience is both stark and moving — an encounter with a form of sacred architecture that breaks decisively with tradition.

Monte Grisa, however, has not been free of troubles. In 2007 part of the roof collapsed, releasing tons of stone and leading to legal proceedings that made headlines for years. Questions of maintenance and safety still linger, as do debates over the sanctuary’s appearance. Some residents cherish it as an icon of Trieste’s skyline; others dismiss it as a brutalist blemish on the landscape. Even practical matters — like the recent failure of the floodlights that once illuminated its silhouette at night, or the removal of benches and tables from its piazzale — have provoked controversy and protest from locals who see such neglect as unworthy of a monument with national and spiritual significance.

For decades there has also been discussion of recognizing Monte Grisa as a cultural treasure beyond its religious role. Proposals to nominate it for UNESCO heritage status point to its unique combination of symbolic origin, architectural daring, and cultural impact. Whether such recognition will ever come remains uncertain, but the conversation itself highlights the sanctuary’s ambiguous place between devotion, architecture, and civic identity.

Today, Monte Grisa continues to embody Trieste’s complexity. It is a place of faith, born of wartime fear and hope, yet also a bold experiment in modern design. It is criticized as cold and admired as visionary, nicknamed with humor and approached with reverence. To stand on its terrace is to see not only the sweep of sea and stone but also the layers of Trieste’s past: its wars, its survival, its playful irreverence, and its ability to live with contradictions.